Will we relive apartheid-style ‘epidemic expediency’ with the coronavirus?

Historians have lessons for us, from the way South Africa has dealt with past epidemics.

- The Monthly Review, Business Day | 7 April 2020

In the Time of Plague: Memories of the ‘Spanish’ Flu Epidemic of 1918 in South Africa, ed Howard Philips (Van Riebeeck Society, 2018, available as an e-book from hipsa.org.za)

Plague, Pox and Pandemics: A Jacana Pocket History of Epidemics in South Africa, by Howard Phillips (Jacana, 2012, available as an e-book from online booksellers)

“The Sanitation Syndrome: Bubonic Plague and the Urban Native Policy in the Cape Colony, 1900-1909”, Maynard Swanson, Journal of African History, XVIII, 3 (1977)

Confined to my home, in comfort, with a full larder and uncapped wifi and a view over False Bay to the Cape Flats, I find myself pondering a question raised by the history I am reading: Where is the line between quarantine and segregation? And another: how does an epidemic change society, or expose its underlying fissures?

The threatening coronavirus epidemic underscores the gross inequality of our society – and this division was actually written into law as a response to previous South African epidemics. In a seminal essay published forty years ago, the historian Maynard Swanson tracked the way the bubonic plague of 1901 was used by the Cape authorities to achieve what they had always desired: “no less than the mass removal of Cape Town’s African population, even though the number of Africans contracting the plague was less than either whites or coloureds…. ”

When whites and coloureds were removed from infected homes in Cape Town, they were taken to an emergency camp but allowed to return after the buildings had been fumigated. But Capetonian “kaffirs” were forced to move permanently, in the interests of public hygiene, to hastily-constructed lean-tos at Uitvlugt on the edge of town. Renamed Ndabeni, this was South Africa’s first township. As the plague spread, carried in fodder for British horses during the South African War, black people would be forcibly removed to settlements outside other towns too: Ginsberg and New Brighton in the Eastern Cape and, to the north, Klipspruit, the seed of Soweto, established after the torching of Coolie Location in Johannesburg.

Before it was set on fire, a cordon sanitaire had been thrown around Coolie Location: all inhabitants were to be treated, the Rand Plague Committee wrote, “as suspects and not as mere contacts,” and not allowed to leave. Watching it go up in flames, a young Indian lawyer named Mohandas K. Gandhi noted that this was “essentially a theatrical display”; one calculated “to reassure white Johannesburg that no stone would be left unturned to safeguard their health,” as Howard Phillips puts it in his Plague, Pox and Pandemics – a short book that is required reading for these times.

Mohandas Gandhi described the torching of Coole Location as a theatrical display meant to reassure white Johannesburg that their health was the priority. (The Graphic, 4 June 1904)

Phillips cites Swanson, who wrote that “it was the merest step of logic to proceed from the isolation of plague victims to the creation of a permanent location for the black labouring class… With the plague emergency the definitive step of quarantine and segregation was taken.” This became apartheid, when black people were only allowed out of what we might call ‘lockdown’ to provide the ‘essential service’ of their labour for whites.

Phillips coins the term “epidemic expediency” to describe the way an epidemic is used to achieve a policy objective beyond that of public health. Examples abound through history, and Philips demonstrates how such expediency was further applied in South Africa seventeen years later, when 300 000 people were killed in just six weeks, in the ‘Spanish’ flu epidemic of 1918. Finally, in 1923, the prime minister Jan Smuts could put into place the Native (Urban Areas) Act, precursor to the Group Areas Act, arguing that it would remove the slums that were “a grievance and a menace to health and decent living in this country.”

D.C. Boonzaier’s chilling cartoon of the Spanish flu in Cape Town. (De Burger, 16 October 1918)

Here is a difficult truth: disease does spread more rapidly in places – call them “slums” or call them “informal settlements” – where there is overcrowding, and where it is so much harder to implement the basic rules of hygiene. For all our romanticization of places like District Six and Sophiatown, we can forget how tough life could be in them, particularly if you were poor, and for this reason, “slum clearance” has always been something of a double-edged term in South African history. Today, as a century ago, the people who live in informal settlements around our cities are not there by choice: they need to be close to work, or to the possibility of it and to services, and this is all they can afford or have access to.

This begs a question for us, today: whether Covid-19 has revealed inequality in a way so stark that those in power can no longer ignore it. The way that they respond –the we respond, readers of Business Day – will be the measure of our “epidemic expediency”.

Such expediency need not only have negative connotations. Phillips gives another, perhaps more constructive, application of the concept, in the way the vaccination against smallpox was used “by medics, missionaries and ministers” to expand the reach of western medicine across the region: “the spread of biomedicine in the 19th Century was led by the tip of a vaccinating lancet.”

Of course, others have noted the sharp point to this lancet, given the missionaries bringing the Bible, and the administrators bringing colonial law, alongside those medics. The racist nature of hygiene discourse in Africa is something Thabo Mbeki loved to cite, for example, in his critique of the way he believed epidemiologists pathologized black sexuality.

“As always, the fear engendered by an epidemic revealed underlying notions of the self and others,” writes Phillips of AIDS. “A very heterogeneous society like South Africa has never lacked for ‘others’ to suspect of difference; what HIV/AIDS and its predecessor epidemics added to this so powerfully was the belief that such difference could be fatal to the rest of society. In this situation, prejudice, stigma and hostility flourished and prompted action.”

If white South Africans tended to blame the unsanitary black people in their cities for spreading disease, then for many traditional Africans, “evil stemmed from the actions of malevolent witches and wizards seeking to destroy them and their families.” And so, in the aftermath of the ‘Spanish’ flu, “professional witch-finders were in high demand to ‘smell out’ those responsible.”

Witch-hunting was a phenomenon of the AIDS epidemic too, and there are, today, the first signs of such stigmatization accompanying the Covid-19 epidemic: last weekend, the Sunday Times reported that two early sufferers and their families, in Khayelitsha and in KwaZulu-Natal, have been ostracized by their communities. In the case of the Khayelitsha woman, her landlady chucked her out, and she was hounded out of the township by negative social media.

“Epidemics do not create abnormal situations but rather sharpen existing behavior[s] which ‘betray deeply rooted and continuing social imbalances.’”

Thus wrote Roderick McGrew, a historian of cholera in Imperial Russia. Citing him in “The Sanitation Syndrome”, Swanson contrasts the way Western liberal states and Russia dealt with cholera in the 19th Century. While in the west, public health programmes were extended and “tended to enhance the governmental assumption of responsibility for social conditions, Russia remained essentially repressive in character, consistent with its fundamental social structure.” The Russian authorities “treated the people as a captive population in a conquered country”, wrote McGrew; they were “better at devising restrictions than at offering positive reforms.”

I have been thinking about these lines, as I have watched different leaders deal with today’s coronavirus. China’s repressive regime meant first that it suppressed information about the epidemic thus allowing it to spread, and then that it was able to control it through fiats to a compliant and fearful citizenry. Meanwhile, the United States is currently unthreading before our eyes because it has no public health system and a president whose only wellness indices are the market and his inexplicably-rising approvals polls.

Germany’s Angela Merkel called for national solidarity against Covid-19: “since the [end of the] Second World War, there has been no challenge to our nation that has demanded such a degree of common and united action.” Crazy Jair Bolsonaro continues to deny the virus as a left-wing plot to his Brazilian rule, and India’s Narendra Modi effectively expelled millions of poor people from the cities with a peremptory lockdown and then put up barriers to prevent them from getting home, leaving them to starve in hastily-erected emergency camps.

In terms of public discourse, we South Africans are mercifully in the Merkel camp. But we have our own internal contradictions, and our epidemic will be unique, not just because of our inequality gap but because one of the consequences of this gap is a population deeply compromised, already, by HIV and tuberculosis. Our lockdown regulations mirror those of Europe, but are ill-suited to the dense urban settlements that really are a “grievance and menace to decent living” in our country. And while health minister Zweli Mkhize’s screening and isolation strategies are laudable, we are, as ever, the victims of another gap in South Africa: that between great ideas at the top, and the ability to implement them on the ground.

Some lines of Swanson on pre-revolutionary Russia, citing McGrew, haunt me: because cholera hit the slums disproportionately, it took on a “class character”. When “the wealthy and civilized” contracted the disease, this “ ‘seemed only to underline the danger of living near the poor…’ The poor on the other hand turned feelings of resentment, suspicion and blame against the wealthy and those in authority, who in turn felt threatened by the menace of social disorder and revolution.”

Any South African response to Covid-19 has to consider this, alongside the public health imperatives.

Howard Phillips is this country’s pre-eminent historian of epidemics. I asked him, in a phone conversation, whether he saw any examples of “epidemic expediency”, yet, in South Africa’s response to Covid-19? I had in mind a niggling anxiety about the government’s decision to access our cellphones to do contact tracing, and how this might conveniently spill into ‘peace-time’ practice if we don’t pay attention.

But Phillips responded with a more tangible, and immediate, example: the removal of protesting refugees, bunkered down in Cape Town’s Central Methodist Church in Cape Town. “The city has been wanting to do this for many weeks, and now, because of the epidemic, the refugees simply can no longer remain in the church. They’ve been removed and placed in camps, and the city has achieved its objective. It’s a textbook case of epidemic expediency.”

Philips told me that there was one primary lesson from 1918: “Social distancing, quarantine and isolation are a sine qua non.” Because infected South African troops who had just returned from Europe to be demobilized were not properly quarantined in 1918, “they spread the disease high, wide and handsome once they were allowed to go home by train. It was like mercury being spilt: it spreads in every direction, unstoppably. That’s what happens when you don’t quarantine effectively.”

To commemorate the centenary of the ‘Spanish’ flu of 2018, Phillips published a collection of interviews he did with survivors from the 1970s onwards, with other archival material. It makes for poignant reading today. As I look outside at the stillness of Cape Town – well, my suburban part of it, anyway – I cannot but think of this description of Bloemfontein in October 1918: “All this week the hand of the disease has lain heavily on the town, and so uncanny was the stillness in the streets and shops that we might have been in a city of the dead.”

The horror of so much death all around them, and the sadness of loss, haunts the memories of Phillips’ informants. But in start contrast to the historian’s objective record of the othering in public discourse, so many of them find solace in the memory of solidarity. Perhaps this is a natural function of nostalgia. Listen, for example, to the African National Congress founder Selby Msimang: “Despite all differences with whites, the ‘Spanish’ flu epidemic created a spirit that was never known before in Bloemfontein. Whites were sympathetic – they became friends and brothers to people in the location….There was a lovely feeling of brotherhood – it never again existed.” Msimang was interviewed by Phillips in 1981, a year before his death. “In these days, with all their uncertainty,” he added ruefully, “perhaps such an epidemic would create a new spirit”.

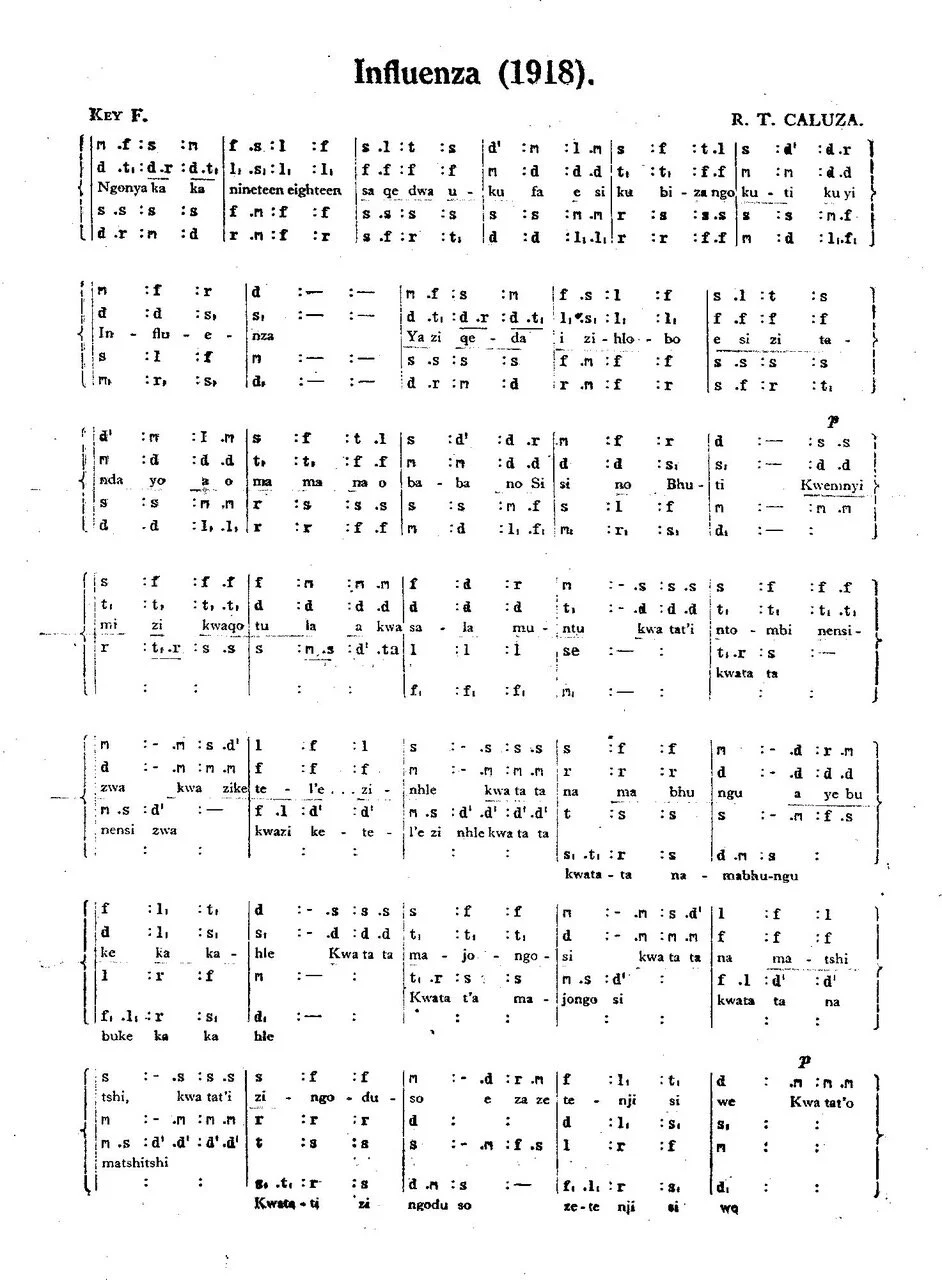

Philips also includes a 1981 interview with a woman named Gertrude Kumalo, who was 25 during the epidemic. She breaks into song, singing by memory a dirge written by the pioneering Zulu composer Reuben Caluza: “Ngonyaka ka nineteen eighteen/ Saqedwa ukufa esikubiza ngokuti kuyi influenza.” (“In 1918 an influenza epidemic spread like wildfire throughout the country. It took with it many lives. Our beloved mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers died. At some homes not a soul survived.”)

Here is the final line, as translated in Phillips’ book: “Therefore, youth, let not hearts be troubled, for there is no complete happiness.”

This seems to me the eternal message of epidemics. “The plague condition is simply a heightened state of the condition of being mortal,” writes J.M. Coetzee of plague literature, from Defoe through Camus to Roth. In a beautiful recent New York Times essay on Camus’ The Plague, the philosopher Alain de Botton agrees: “For Camus…. there is no escape from our frailty. Being alive always was and will always remain an emergency; it is truly an inescapable ‘underlying condition.’ Plague or no plague, there is always, as it were, the plague, if what we mean by that is a susceptibility to sudden death, an event that can render our lives instantaneously meaningless.”

For De Botton, “this is what Camus meant when he talked about the ‘absurdity’ of life. Recognizing this absurdity should lead us not to despair but to a tragicomic redemption, a softening of the heart, a turning away from judgment and moralizing to joy and gratitude.”

Howard Phillips has sent me a 1930 recording of “Influenza”, by Caluza’s own choir, and I am listening to it right now. It is disconcertingly jaunty, and as I look out across the dead-still city I choose to hear the soothing hope of its last line. And of its author’s own extraordinary life: a legend in choral music, he managed to get a master’s degree in music from an American university, even as his life as a black South African was challenged by the epidemic expediency of apartheid.

Reuben Caluza (r) wrote “Influenza” during the 1918 ‘Spanish Flu’ epidemic.